The changing climate is affecting critical cultural and community resources, species, habitats, people, and assets.[1] In many cases, these changes are likely to be profound, having the potential to significantly affect the lifeways of Indigenous communities. Yet, since time immemorial, Tribes have maintained their cultural traditions, demonstrating a high degree of resilience in the face of changing environmental and social conditions.[2]

The Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook, published as a pdf in 2018 and adapted to a website in 2022, supports Tribes in their efforts to prepare for climate change. The Guidebook provides a comprehensive framework for climate change adaptation planning that explicitly recognizes the distinct circumstances of Tribal governments, culture, and knowledge systems while highlighting exemplary efforts by Tribes to adapt to climate change.

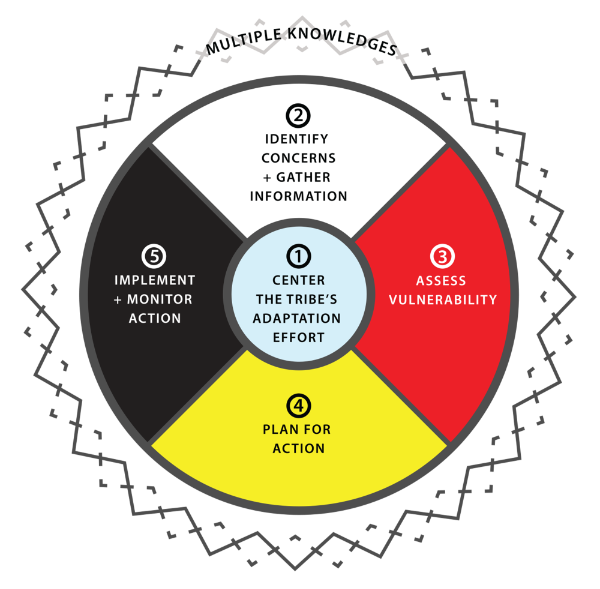

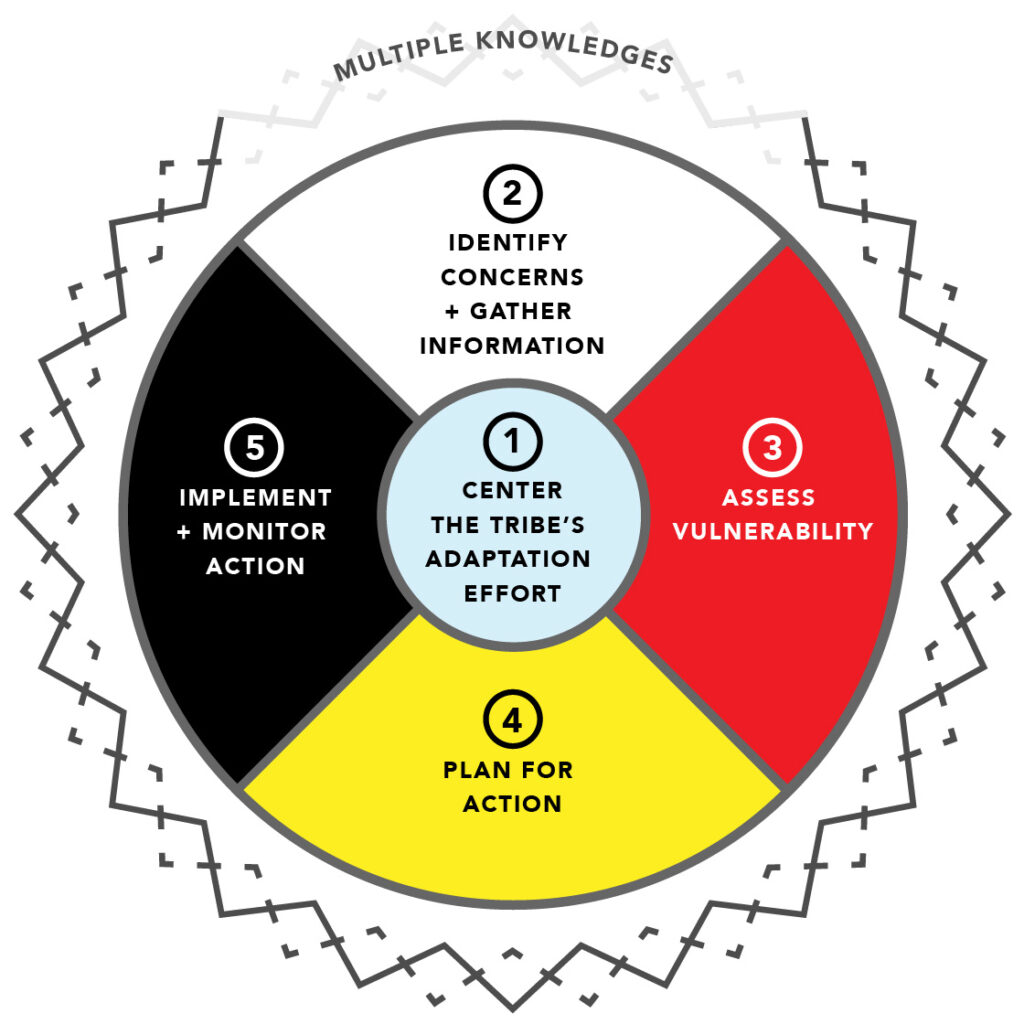

The Guidebook’s framework has five major steps:

- Step 1: Center the Tribe’s Adaptation Effort,

- Step 2: Identify Concerns and Gather Information,

- Step 3: Assess Vulnerability,

- Step 4: Plan for Action, and

- Step 5: Implement and Monitor Actions.

Each step is broken down into a number of activities. Embedded within each activity are suggested tasks, guidance on incorporating and protecting Traditional Knowledges, guiding questions, Tribal examples, resources, and additional tips on engaging the Tribal community and documenting the adaptation planning process. The Guidebook and website were created by the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute at Oregon State University and Adaptation International along with multiple contributors.

“In the Upper Snake River Watershed, this time-period [the last 10,000 years] included: a transition out of an ice age; mass emergence and migration of plants and animals; and the collision of societies, materials and goods, and disease from the opposite side of the world. USRT [Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation] member Tribes now face the environmental, societal, and cultural effects of human-driven global climate change and will look both to their proven cultural strengths and the adoption of innovative techniques to continue to successfully adapt and thrive on the landscape.”

—Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

Indigenous peoples have lived on and with the land since time immemorial. Through the impacts of settler colonialism, genocide, and forced removal from Native homelands, Indigenous peoples have endured undue hardships that have resulted in social conditions that limit Tribal capacity for resilience.[3] Many Tribes are still rebuilding their Nations, prioritizing issues such as enhancing health, reducing poverty, decreasing homelessness, increasing support for veterans, improving education, protecting reserved rights, and asserting their sovereignty.

The effects of climate change interact with other existing social, political, economic, and environmental changes, and can exacerbate current stressors or create cascading effects.[4] Indigenous peoples are impacted by climate change at disproportionately higher rates than other populations. In addition, many Tribal communities are located in geographically vulnerable environments, making them more exposed and sensitive to climate change.[5] Climate change stands to affect Tribal sovereignty and self-determination, Tribal culture, and the community health of Indigenous peoples.[6]

As sovereign governments, federally recognized Tribes have a government-to-government relationship with the United States federal government. This relationship entails a trust responsibility to protect the treaty rights, lands, assets, and resources of federally recognized Tribes.[7] Climate change threatens Tribal sovereignty and self-determination by potentially affecting treaty and reserved rights, including subsistence rights and access to traditionally significant plant, animal, and aquatic species.

As climate change alters the land, ecosystems, and species distributions, Tribes with resource-based livelihoods may lose access to natural resources within traditional homelands, Usual and Accustomed areas, and ceded or ancestral territories.[8] Climate change also negatively impacts Tribal community health and well-being—which involves the interconnection of social, cultural, spiritual, environmental, and psychological health—through reductions in the quality and quantity of or access to culturally important species, subsistence foods, and traditional nutrition sources.[9]

“We live in harmony with the land and the environment and the sustenance that is provided by our lands, and with the gifts of life sustainability come the responsibility to protect the land, water and environment from which we maintain our livelihood. In [our adaptation plan], we hope to use the traditional ecological knowledge of our elders who have lived long lives and have seen the changes over time[.]”

—Harry Barnes, Chairman Blackfeet Tribal Business Council, Blackfeet Climate Change Adaptation Plan

Each Tribe has a unique system of gathering, organizing, interpreting, applying, and sharing knowledge related to their people, culture, and traditions. This body of knowledge and these knowledge systems can be described as “Traditional” or “Indigenous” knowledges. These knowledges refer to “ways of knowing” that “can encompass culture, experiences, resources, environment, and animal knowledge” that “are passed down generationally from elder to youth through oral histories, stories, ceremonies, and land management practices.”[10]

By providing observational evidence and informing the development of adaptation strategies that are culturally appropriate, Traditional Knowledges (TKs) are essential to Tribal understanding of climate change. Yet, TKs are eroding as environmental changes and the timing of traditional ecological events become less reliable in determining the timing and practice of traditional and cultural activities.[11]

The Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives refers to TKs as “[I]ndigenous communities’ ways of knowing that both guide and result from their community members’ close relationships with and responsibilities towards the landscapes, waterscapes, plants, and animals that are vital to the flourishing of [I]ndigenous culture.”[12] These traditional information systems are held by Tribal members and shared through Tribal community, cultural practices, oral history, as well as direct family lineage, across multiple generations over long periods of time. TKs encompass many aspects of traditional practices and cultural information, not only but including environmental knowledges. The term Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) refers to application and utilization of these generationally based TKs with natural resources on the landscape in management, collection, ceremonial sustainability efforts, or reciprocity behaviors and practices. TEK was first coined as the “cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.”[13]

Traditional Knowledges encompasses a wide variety of overarching traditional practices that are foundational bases for traditional culture. Traditional Knowledges may include, but is not limited to: storytelling, seasonality, phenology, identification of cultural items, patterns, or traditions, and genealogy. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is the application of the specific area of Traditional Knowledges and Indigenous Science that relates to the environment and ecology, including botanical knowledge, medicinal application (collection and/or administration), hunting, fishing, gathering, processing of material(s), caretaking (such as burning, coppicing, thinning), astronomy, phenology, ecological markers, species markers, and weather and climate knowledge.[14]

This Guidebook recognizes that the terms Traditional Knowledges and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are defined and manifested differently among different Tribes and knowledge holders.

Throughout this Guidebook, the term TKs is used to include both environmentally focused and non-environmentally focused TKs. Tribal community members, staff, and leadership in most cases have already noticed changes to the environment or recent, novel extreme weather events. Other noted observations may include shifts in the patterns and/or timing of important environmental events; and how drought, extreme heat, or heavy rainfall events may have affected species, habitats, as well as community and cultural resources important to the Tribe. These observations and relevant TKs that support Tribal culture and traditions can be identified and applied to climate change adaptation as appropriate.

Deciding how and where it is appropriate to incorporate TKs is a decision that can only come from each Tribal government and knowledge holder. A knowledge holder is most often a Tribal member who has been imparted with and/or actively participates in TK and/or TEK activities based on generations-worth of information.

When working with partners outside the Tribe, sharing TKs requires approval from governing entities such as specific committees and Tribal leadership. Tribes maintain the right not to share TKs with external partners but could incorporate those knowledges separately as part of their internal planning process. Tribes and knowledge holders have the right to decline to share TKs and should only share TKs with free, prior, and informed consent.[15]

It is important to identify Tribal policies concerning and addressing Tribal Intellectual Property Rights, which can include oral traditional information, and understand the Tribe’s legal processes for addressing the information, which is sometimes prevented from general public release along with the legal restrictions of these Tribal intellectual properties.

Using TKs in climate change planning can benefit the Tribe, promote greater collaboration with partners, and improve the outcomes of adaptation planning. Generational oral tradition information is not necessarily termed “Traditional Knowledges” or “Traditional Ecological Knowledges,” but acknowledged as a traditional information system without labels. Many Tribes have already incorporated information that is pertinent to their Tribe and TKs into Tribal policies and procedures.

“We’ve always been good at adaptation. You look at the 500 years that the western civilizations have been here… And the Tribes are probably one of the best adapters of being able to survive right along next to the western cultures.”

—Swinomish Indian Tribal Community member, Swinomish Climate Change Initiative Climate Adaptation Action Plan

“Our Tribes are strong and resilient people. We have lived on these lands for countless generations, from time immemorial. We will continue to flourish on our homelands for countless generations to come.”

— Climate Adaptation Plan for the Territories of the Yakama Nation

“Adaptation has long been part and parcel of indigenous communities; indeed their very survival and continuity as peoples depended on successful response to change.”

—Gary S. Morishima, Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Primer

Adaptation is the processing of culturally relevant information and practices while implementing a suite of actions to better prepare for and adjust to new conditions while maintaining cultural protection in order to reduce risk, utilize new opportunities, and enhance resilience. Resilience is the capacity of a community to withstand, survive, and thrive by applying adaptation actions that maintain and adhere to essential cultural functions, identities, and structures while co-existing with and managing for changing conditions.[16] Indigenous resilience may include protecting, preserving, and enhancing Tribal resources, cultural and Traditional Knowledges and practices, identity, and sovereignty in the face of climate and other changes.

Despite facing disproportionate impacts from climate change, Tribes have demonstrated leadership in building resilience by actively responding and adapting to climate change.[17] Tribes are on the frontlines of changing conditions, have deep cultural and spiritual connections to natural resources, continue to articulate and adapt to these same impacts for much longer than recognized from a Western perspective, and recognize the importance of taking action to ensure a better future for the next generations. Tribes use multiple avenues to achieve and maintain resilience. These approaches are often multi-tiered, have far-reaching effects as they have been passed down generationally, and often are not identified by labels or titles in the same manner as Western science. At the foundation of Native resilience are Traditional Knowledges and Traditional Ecological Knowledges, or knowledge-based practice.[18]

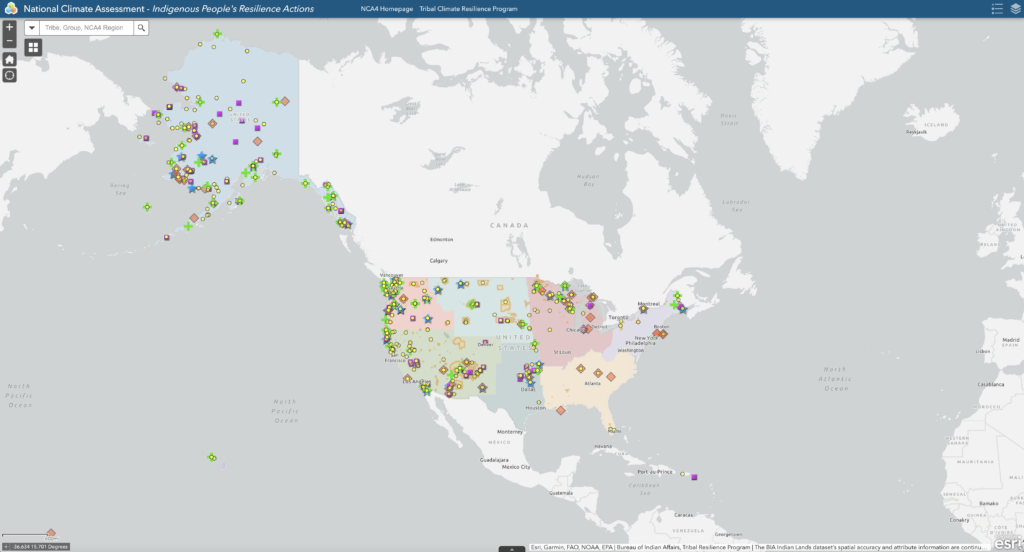

Tribes across the country have proactively developed Tribal climate adaptation plans and other resilience actions with the support of federal funding opportunities, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Tribal Climate Resilience Program, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, other federal agencies, and non-federal partners (Figure 1).

The BIA Tribal Climate Resilience Program was established in 2011 to enable climate considerations to be incorporated into Tribal resource management planning and decision-making. From 2011 through 2022, the Tribal Climate Resilience Program has awarded $74 million to Tribes and organizations supporting more than 250 Tribal adaptation plans, vulnerability assessments, and risk assessments, according to numbers provided to this Guidebook from the BIA. Grants have funded a range of activities, including travel expenses (so that Tribal staff could attend climate change training courses) and financial support for climate change vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans. A list of Tribal climate resilience programs, reports, and actions can also be found on the University of Oregon Tribal Climate Change Guide.

Figure 1. US Indigenous Peoples Resilience Actions.

Tribal climate projects funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, other federal agencies, and other non-federal partners. Activities shown include projects focused on planning and assessment (orange dots); adaptation and implementation (red dots); monitoring and research (green dots); governance and capacity building (gray dots); and youth or traditional knowledges (blue dots). Additional projects for the Pacific Islands and Caribbean are available online.Visit the source website for further context and details.[19]

Tribes also recognize the importance of working together to enhance resilience by jointly addressing climate change-related vulnerabilities. Regional inter-Tribal groups support information sharing and learning between Tribes working on climate change. Tribal organizations supporting information sharing include: the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians; Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission; Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission; Point No Point Treaty Council; the Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation; the Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan; and the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission. This work is further facilitated by networks, including: the Pacific Northwest Tribal Climate Change Network and the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals.

“I don’t believe in magic. I believe in the sun and the stars, the water, the tides, the floods, the owls, the hawks flying, the river running, the wind talking. They’re measurements. They tell us how healthy things are. How healthy we are. Because we and they are the same. That’s what I believe in.”

—Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually Tribe[20]

“The Tribes believe everything in nature is embodied with a spirit. The spirits are woven tightly together to form a sacred whole (the Earth). Changes, even subtle changes that affect one part of this web affect other parts. Protecting land-based cultural resources is essential if the Tribes are to sustain Tribal cultures.”

— Climate Change Strategic Plan for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation

One of the first adaptation guidebooks, Preparing for Climate Change: A Guidebook for Local, Regional, and State Governments, was devised as a partnership between the University of Washington and King County, Washington in 2007.[21] This guidebook outlines a helpful set of steps that a local government could follow to conduct a vulnerability assessment and develop an adaptation plan. Though intended primarily for Western local municipal governments, the guidebook has been used around the world, including by Native American Tribes. There are several other adaptation guidebooks designed to incorporate climate change adaptation planning into: federal and state land management;[22] conservation planning for fish, wildlife, and habitats;[23] and provide local governments an adaptation framework.[24] Still other guidebooks are designed to empower communities to plan for climate change.[25] Most of these guidebooks are written from a perspective of Western science and culture. While valuable, these materials typically do not recognize the unique conditions of Tribal governments and cultures.

At the same time, many Tribes across the country have been leading exemplary efforts to address climate change. There are also several organizations providing various types of support and resources for Tribal climate change adaptation planning.

This Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook builds on the ongoing climate-related work in Tribal communities, provides a framework for climate change adaptation planning in the context of existing Tribal priorities, and directly considers the unique issues facing Indigenous communities. Specifically, this Guidebook directs readers to the foundation of existing resources and Tribal adaptation efforts. It identifies opportunities for braiding together Traditional Knowledges and Western science in developing adaptation plans. The framework outlined here will be useful for Tribes in different phases of climate adaptation planning efforts. The framework also supports learning from the experiences, approaches, and lessons of Tribes working to become more resilient to climate change. The Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook is designed to support Tribes’ efforts to proactively adapt to climate change and thrive for generations to come.

This Guidebook Website (www.tribalclimateadaptationguidebook.com) was created by the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute. No Tribal logos, Tribal photographs, or content from Tribal climate vulnerability assessments or adaptation plans may be used without the express written permission of the owners of those materials. All other elements of the website are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. Reusers may distribute, remix, adapt, and build on the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes, provided that attribution is given to the creator. Any material that is remixed, adapted, or built on must be licensed under identical terms.

This Guidebook follows a holistic approach to adaptation planning called community-driven climate resilience planning. Community-driven climate resilience planning is “the process by which residents of vulnerable and impacted communities define for themselves the complex climate challenges they face, and the climate solutions most relevant to their unique assets and threats.” [26]

There is a range of terminology applied to this type of planning. In this Guidebook, the term adaptation planning is used while recognizing that Tribes can identify and employ terms that resonate most for them. Broadly, this Guidebook begins by drawing on the Tribe’s unique vision, context, and culture to arrive at a set of Tribal priorities. The Tribe then assesses the vulnerability of these priorities and develops appropriate solutions. Finally, the framework provides strategies to build capacity and implement solutions.

Step 1 offers guidance to Center the Tribe’s Adaptation Effort in the Tribe’s vision and priorities. Also covered in Step 1 is guidance on engaging Tribal leadership and community members and ways the Tribe may consider incorporating Traditional Knowledges in climate change adaptation planning.

The next four steps constitute the climate adaptation planning process: Identify Concerns and Gather Information (Step 2), Assess Vulnerability (Step 3), Plan for Action (Step 4), and Implement and Monitor Actions (Step 5). Each step is connected to and emanates from the Tribe’s vision and priorities and considers multiple knowledges and perspectives (Figure 2). These steps are iterative and cyclical and may need to be revisited periodically through the adaptation planning process.

Figure 2. Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook Framework

A visual outline of the climate change adaptation planning framework presented in the Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook.

The Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook can be used by Tribes at various stages of adaptation planning, from those that have worked in this area for years to those that have not yet formulated or initiated a plan. It can help not only those who are well-resourced, but also in situations where a single Tribal staff member may be tasked with outlining an adaptation plan. The Guidebook need not be followed in sequential order, nor in its entirety. Adaptation planning does not always happen in order and often follows available funding. The Guidebook is designed so that Tribes can work through any applicable section and skip sections that are not applicable.

Throughout the Guidebook, the reader will encounter several features:

- Checklists—suggested activities and tasks within each step. Click the icon at the beginning of each step to download an easy-to-use checklist to print and work through the step.

- Guiding Questions—helpful questions to consider within each activity.

- Traditional Knowledges—considerations for integrating and protecting TKs throughout the adaptation planning process relying on the Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives. References to specific guidelines and actions are denoted by number (e.g., CTKW Guideline 4).

- Tribal Examples—Tribal examples illustrating a particular activity (individual Tribe’s plans and locations within the text where they are cited as an example can be found in Tribal Examples).

- Resources—external resources providing greater context or more specific guidance on a particular aspect of adaptation planning (a compilation of resources is found in Resources).

- Checkpoints—additional tips to sustain two ongoing themes throughout the Guidebook.

- Community Engagement—opportunities and strategies to engage the Tribal community in the adaptation planning process.

- Documentation—opportunities to document the status of the adaptation planning process.

The development of the Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook pdf (2018) and website (2022) was informed, guided, and enriched by a team of advisors along with a group of reviewers and contributors. The content writers and web development staff are indebted to their service to help produce a rich resource that we hope Tribes across the country will find useful.

Content Writers and Web Development Staff

- Meghan Dalton*#, Oregon Climate Change Research Institute, Oregon State University

- Samantha Chisholm Hatfield* (Siletz, Cherokee), Oregon State University

- Alexander “Sascha” Petersen*#, Adaptation International

- Nyssa Russell#, Adaptation International

- Alex Basaraba#, Adaptation International

- Daniel Bisett#, We Rock DM & Adaptation International

*2018 pdf #2022 website

The Oregon Climate Change Research Institute (OCCRI) was established by the Oregon State Legislature in 2007 to assess the state of climate change science, including biological, physical, and social science, as it relates to Oregon and the likely effects of climate change on the state. OCCRI is hosted by Oregon State University’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences.

Adaptation International is a mission driven organization that partners with Tribal and western communities to build resilience to climate change. Adaptation International uses collaborative approaches to connect the best available science and tools with local and Traditional Knowledges to empower communities to be holistic, equitable, and adaptive. Adaptation International can be reached at Contact(at)Adaptationinternational.com.

We Rock DM is an Austin-based digital marketing agency for businesses that want to stand out from the crowd. They primarily provide website development, branding, and digital marketing services for small to medium-sized businesses across the globe.

Advisors

Advisors supported writing staff by refining the goals and objectives for the Guidebook pdf and website and by providing regular reviews throughout the development process.

- Lisa Bacanskas#, Environmental Protection Agency

- Malinda Chase#, Tribal Liaison Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center (Tribal Learning Network)

- Samantha Chisholm Hatfield#, Oregon State University

- Hansi Hals*, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

- Joe Hostler*, Yurok Tribe

- Carolyn Kelly*, Quinault Indian Nation

- Krista Keeringa#, Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center (Tribal Learning Network)

- Kathy Lynn*#, Pacific Northwest Tribal Climate Change Project, University of Oregon

- Philip Mote*, Oregon Climate Change Research Institute, Oregon State University

- Amber Nashoba#, University of Alaska Anchorage

- Rachael Novak#, Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Raymond Paddock III*, Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Tribes

- Daniel Ravenel*#, Quinault Indian Nation

- Gabe Sheoships*, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

- April Taylor#, Tribal Liaison South Central Climate Adaptation Science Center

- Althea Walker#, Climate Science Alliance

- Stan van der Wetering*, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians

- Emma Zinsmeister#, Environmental Protection Agency

*2018 pdf #2022 website

Reviewers and Contributors

Reviewers and contributors provided written or oral comments and suggestions for improvement on a pre-release version of the Guidebook pdf or beta versions of the website.

- Crystal Barnes*

- Arwen Bird*

- Erica Bollerud*

- Sara Brennan*

- Haley Case-Scott*

- Michael Chang*

- Michelle Fox*

- Nathan Gilles*

- Miles Gordon*

- Michael Griffin#

- Holly Hartmann#

- Sharon Hausam*#

*2018 pdf #2022 website

- Mark Healy#

- Margaret Herzog*

- Jennie Hoffman*

- Robert Knapp#

- Dana Krishland*

- Mary Mahaffy*

- Maggie Massey*

- Thomas Miewald*

- Thomas Moore#

- Gary Morishima*

- Ellu Nasser*

- Rachael Novak*

- Susan Osredker#

- James Rattling Leaf Sr.*

- David Reinert*

- Gwen Shaughnessy#

- Sara Smith#

- Missy Stultz*

- Stefan Tangen#

- Bree Turner#

- April Taylor*

- Emma Zinsmeister*

- David O’Donnell*

Tribal Examples

We acknowledge the wealth of Tribal adaptation plans from Tribes across the country from which we were able to draw noteworthy Tribal examples of the adaptation planning process to highlight in the Guidebook. See all Tribal Examples.

Photography

We are grateful to the talented photographers who shared their work to be used in the Guidebook. A very special thank you to the International League of Conservation Photographers and to the following:

• Alexis Malcomb

• Betty Oppenheimer (Jamestown S’Klallam)

• Chas Jones

• Chip Thomas

• David Thoreson

• Hansi Hals (Jamestown S’Klallam)

• Herman Fillmore (Washoe)

• John Gussman (Jamestown S’Klallam)

• Justin Taus

• Karen Kasmauski/iLCP

• Mason Cummings

• Peter Mather/iLCP

• Samantha Chisholm-Hatfield (Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and Cherokee)

• Weronika Murray

• Will Williamson

Home Page: ©Chas Jones. Participants of the 2018 “Power Paddle to Puyallup” carry a traditional Haisla canoe carved in 1934 called Hunclee-quilas or Han-Tli-Kwe-Lough, in honor of the Chief who first established Kitamaat Village. The canoe was one of 120 tribal canoes – some more than 60 feet long and over 2000 lbs – used to honor the theme of 2018’s canoe journey “Honoring our Medicine.”

Step 1 Hero Image: ©John Gussman

Step 2 Hero Image: ©Peter Mather/iLCP

Step 3 Hero Image: ©Peter Mather/iLCP

Step 4 Hero Image: ©Karen Kasmauski/iLCP

Step 5 Hero Image: ©Peter Mather/iLCP

About Page Hero Image: ©John Gussman

Traditional Knowledges Page

• Traditional Knowledges Hero Image: ©Lac du Flambeau

• Image 1: ©Herman Fillmore. Cale Pete, an Environmental Specialist with the Washoe Tribe examines reforested land on Washoe lands.

• Image 2: ©Sam Loveland/Pexels.com.

• Image 3: ©Betty Oppenheimer. Mark Becker of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe adjusts fishing nets from a boat with Mount Baker in the background.

Tribal Example Pages

• Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes – ©Michael Durglo. Stephen Small Salmon and Piper Espinoza of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

• Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe – ©Betty Oppenheimer. Mark Becker of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe adjusts fishing nets from a boat with Mount Baker in the background.

• Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians – ©Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

Funders

The development of the interactive website was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration via the Climate Impacts Research Consortium (NA15OAR4310145 and NA20OAR4310145A). The Guidebook content was initially supported by a grant from the North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative to OCCRI and Adaptation International.

- actionable information—Information at a sufficient timescale, resolution, and certainty that it can inform decisions.

- adaptation—Processing culturally relevant information and practices while implementing a suite of actions to better prepare for and adjust to new conditions while maintaining cultural protection in order to reduce risk, utilize new opportunities, and enhance resilience.

- adaptation action—A specific activity that can be implemented in order to achieve adaptation goals.

- adaptive capacity—The ability to adjust to potential impacts, take advantage of opportunities, and respond to extreme weather events and changing climate conditions.

- adaptation goal—General statement about what the tribe wants to accomplish in a priority planning area.

- adaptation plan—Documentation of how an entity identifies and assesses the vulnerability of key concerns and planning areas that are likely to be affected by changing climate conditions; develops adaptation goals and actions to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience; and establishes a plan to implement and monitor success of adaptation actions.

- adaptation planning—The process by which an entity identifies and assesses the vulnerability of key concerns and planning areas that are likely to be affected by changing climate conditions; develops adaptation goals and actions to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience; and establishes a plan to implement and monitor success of adaptation actions.

- climate exposure—An extreme weather event or changing climate condition that could adversely affect people, livelihoods, species, ecosystems, environmental functions, services, resources, infrastructure, and economic, social, and cultural assets.

- climate projections—The simulated response of the climate system (e.g., temperature, precipitation, etc.) to a scenario of future emissions or concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols, generally derived using global climate models.

- community engagement—The facilitation of purposeful reflection and discussion among tribal community members about topics of common concern and decision-making.

- emissions scenario—A plausible representation of future emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols based on a coherent and internally consistent set of assumptions about driving forces such as demographic and socio-economic development, technological change, energy use, and land use.

- global climate models—Numerical computer representations of the Earth’s atmosphere, water, and land based on physical, chemical, and biological properties, and how these components interact over time and space.

- goal—General statement about desired long-term outcomes.

- indicators of success—Measurable characteristics of implementing adaptation actions that can be monitored over time.

- key concerns—The natural and built resources, assets, and issues that are most important to the tribe, have the potential to be affected by climate change, and can be addressed within the scope of available resources and capacity.

- mainstreaming—An approach to adaptation planning that involves integrating climate adaptation into existing management functions and planning efforts.

- objective—Specific statement focused on how to achieve a specific goal.

- planning areas—Sectors or systems that mirror the tribe’s governance and management structure or important ecosystem and human systems.

- resilience—The capacity of a community to withstand, survive, and thrive by applying adaptation actions that maintain and adhere to essential cultural functions, identities, and structures while co-existing with and managing for changing conditions. Indigenous resilience may include protecting, preserving, and enhancing tribal resources, cultural and traditional knowledge and practices, identity, and sovereignty in the face of climate and other changes.

- risk assessment—The process of identifying the probability of occurrence multiplied by the magnitude of impact of an adverse event.

- sensitivity—The degree to which a species, asset, or resource is affected by an extreme weather event or changing climate conditions.

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)—Complex and multifaceted Indigenous knowledge systems based in Traditional Knowledges that are often direct application and utilization of Traditional Knowledges having to do with ecology, ecosystems, or the environment.

- Traditional Knowledges (TKs)—Complex and multifaceted Indigenous knowledge systems encompassing many aspects of traditional practices and cultural information.

- transformational adaptation—Taking actions that move beyond incremental changes to existing systems and include consideration of system-wide changes or changes across more than one system; focus on long-term change; and directly question the effectiveness of existing systems, social injustices and power imbalances.

- vulnerability—The degree to which a key concern is susceptible to adverse effects of climate change as determined by climate exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.