“TKs [Traditional Knowledges] and western science each have their own strengths and weaknesses; neither is superior to the other. Braided together, both can retain their own identity while strengthening the whole body of knowledge regarding climate science.”

—Gary S. Morishima, Quinault Management Center, Quinault Indian Nation, Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Primer

Each Tribe has a unique system of gathering, organizing, interpreting, applying, and sharing knowledge related to their people, culture, and traditions. This body of knowledge and these knowledge systems can be described as “Traditional” or “Indigenous” knowledges. These knowledges refer to “ways of knowing” that “can encompass culture, experiences, resources, environment, and animal knowledge” that “are passed down generationally from elder to youth through oral histories, stories, ceremonies, and land management practices.”[1]

The Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives (summarized below) refers to TKs as “[I]ndigenous communities’ ways of knowing that both guide and result from their community members’ close relationships with and responsibilities towards the landscapes, waterscapes, plants, and animals that are vital to the flourishing of [I]ndigenous culture.”[2] TKs encompass many aspects of traditional practices and cultural information, not only but including environmental knowledges. The term Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) refers to application and utilization of these generationally based TKs with natural resources on the landscape in management, collection, ceremonial sustainability efforts, or reciprocity behaviors and practices. This Guidebook recognizes that the terms Traditional Knowledges and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are defined and manifested differently among different Tribes and knowledge holders.

Using TKs in climate change planning can benefit the Tribe, promote greater collaboration with partners, and improve the outcomes of adaptation planning. Generational oral tradition information is not necessarily termed “Traditional Knowledges” or “Traditional Ecological Knowledges,” but acknowledged as a traditional information system without labels. Many Tribes have already incorporated information that is pertinent to their Tribe and TKs into Tribal policies and procedures. Deciding how and where it is appropriate to incorporate TKs in climate change initiatives is a decision that can only come from each Tribal government and knowledge holder.

As the Federal Government works with Tribes on climate change initiatives that involve Traditional Knowledges, federal agencies have a role in ensuring that Traditional Knowledges are given proper weight in climate initiatives, considered in culturally appropriate ways and incorporated with the free, prior, and informed consent of Tribes and knowledge holders.[3] A report, Tribal Climate Change Principles: Responding to Federal Policies and Actions to Address Climate Change, was developed in 2015 to provide information and guidance to the federal government when dealing with impacts of environmental change on Indigenous peoples and to increase understanding and respectful relationships among participants involved in federal and other initiatives. One of the eight principles included in the report states that “Indigenous Traditional Knowledges, with the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples, must be acknowledged, respected, and promoted in federal policies and programs related to climate change.” The report proposes that federal agencies adopt the Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives.

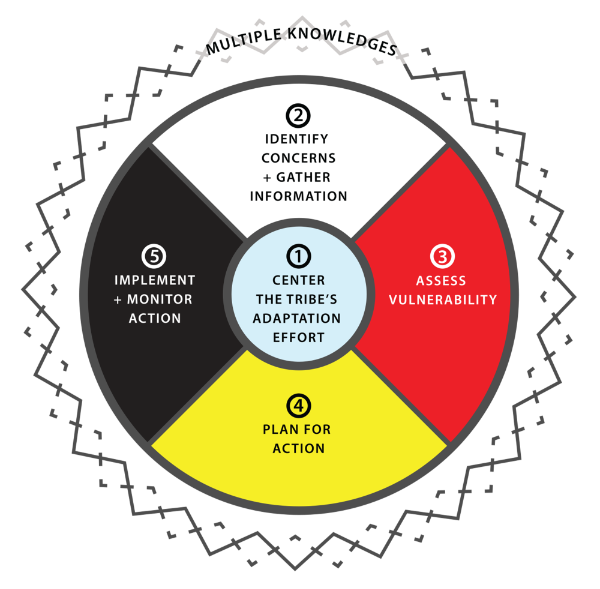

The Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives is a set of guiding principles and suggested actions for both Tribes and non-Tribal partners in order to minimize the risks involved with sharing TKs with non-Tribal partners in climate change initiatives. The Climate and Traditional Knowledges Workgroup (CTKW), consisting of Indigenous scholars and other experts working with issues of TKs, recognizes that knowledge sharing in this context is an ethical issue and developed the Guidelines in 2014 “to raise awareness of potential risks to Indigenous peoples and potential options for best practices.” The Guidelines rest on two principles for engagement: Cause No Harm and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). The executive summary of the Guidelines is reproduced with permission below. The full pdf of the Guidelines can be downloaded from the CTKW’s website. Each activity in the Tribal Climate Adaptation Guidebook includes considerations for integrating and protecting TKs throughout the adaptation planning process that rely on these Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges (TKs) in Climate Change Initiatives.

Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges

These guidelines are intended to provide specific measures that federal agencies, researchers, Tribes and TK holders can follow in conceptualizing, developing, and implementing climate change initiatives involving TKs. The actions in these guidelines are not comprehensive, and are not in any way intended to supersede the obligation of federal agencies to consult Tribes and TK holders with whom they are collaborating or amend or modify any agreements that may exist between Tribal governments and federal entities. These guidelines are intended to promote the use of TKs in climate change initiatives in such a way as to benefit Indigenous peoples, promote greater collaboration between federal agencies and Tribes, and increase Tribal representation in federal climate initiatives. These guidelines are a work in progress.